Lack of Awareness and Knowledge

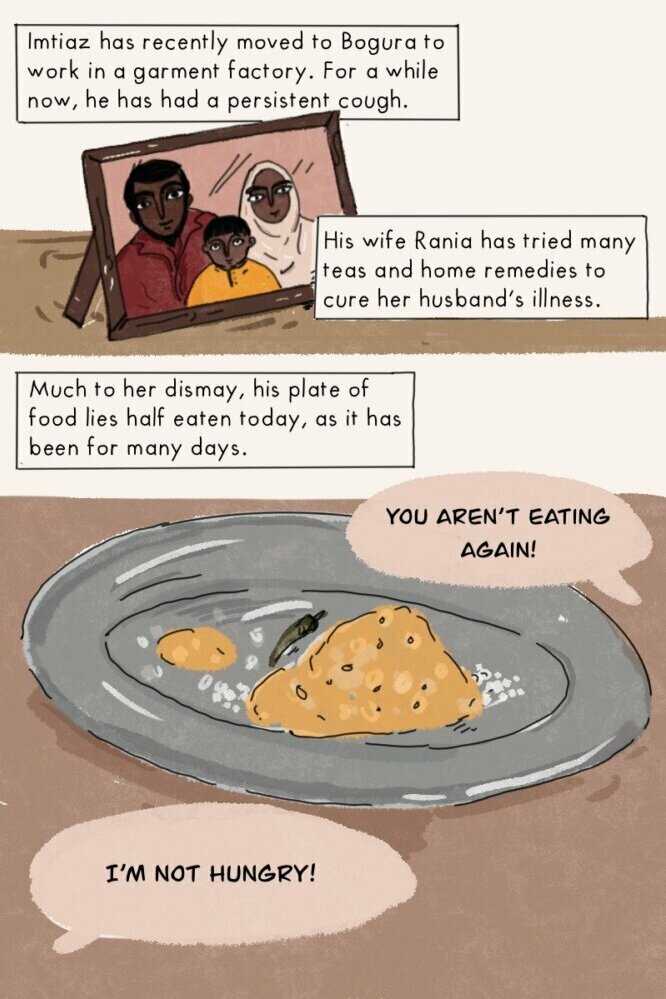

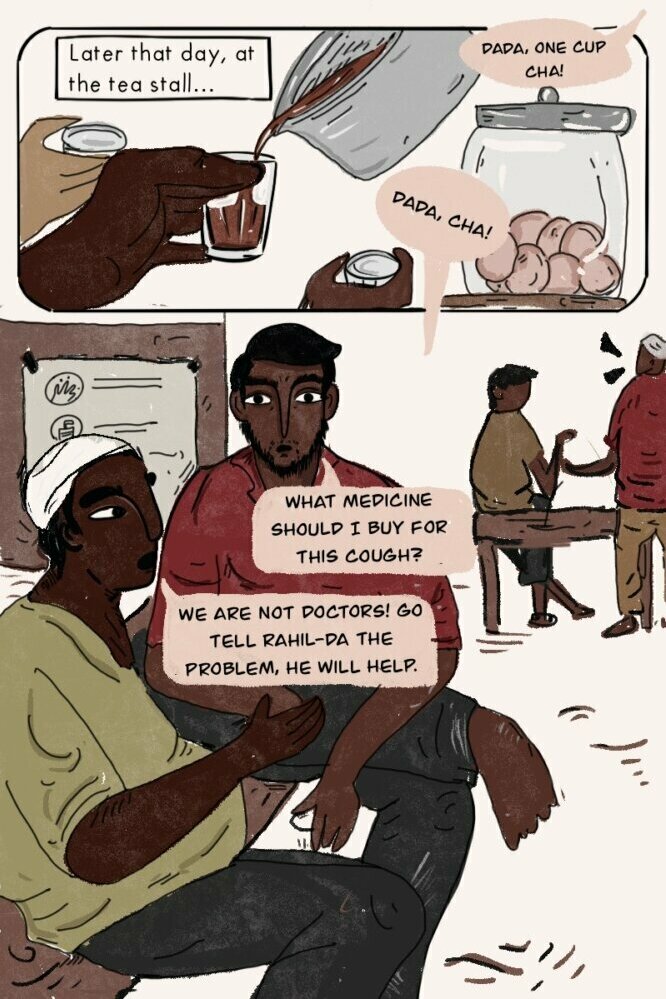

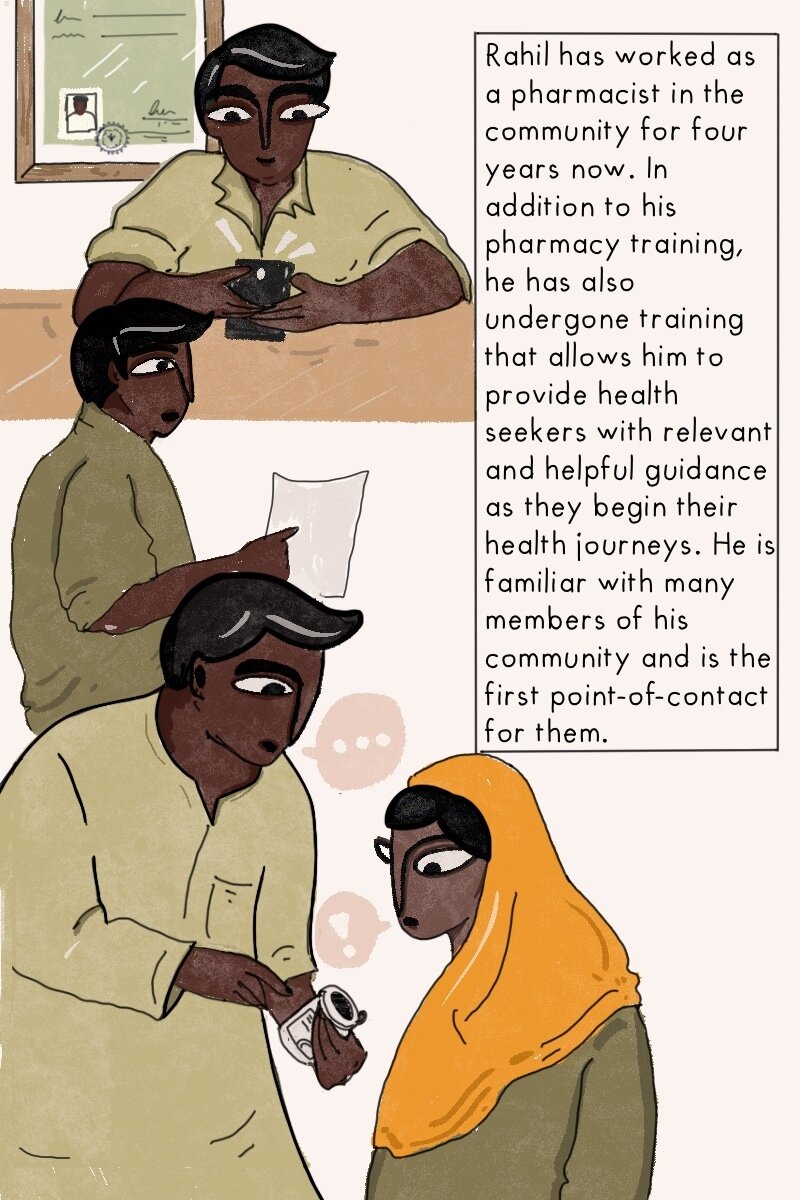

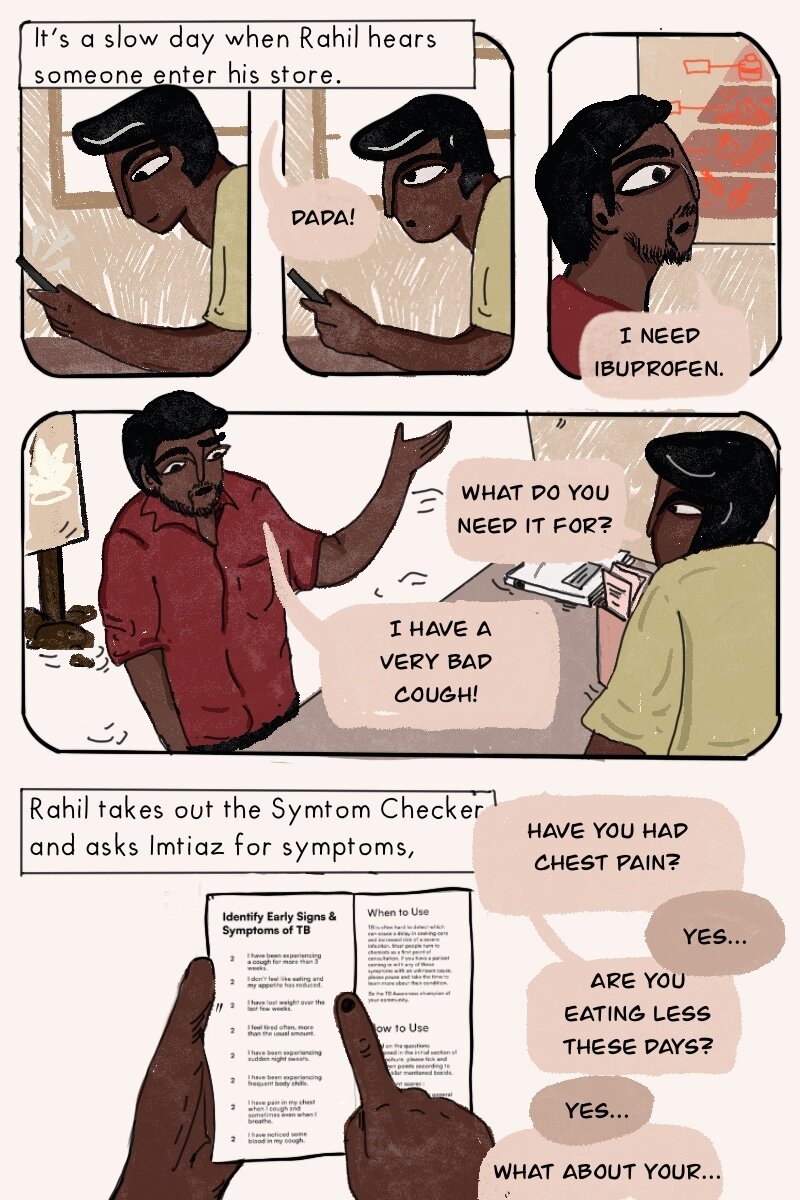

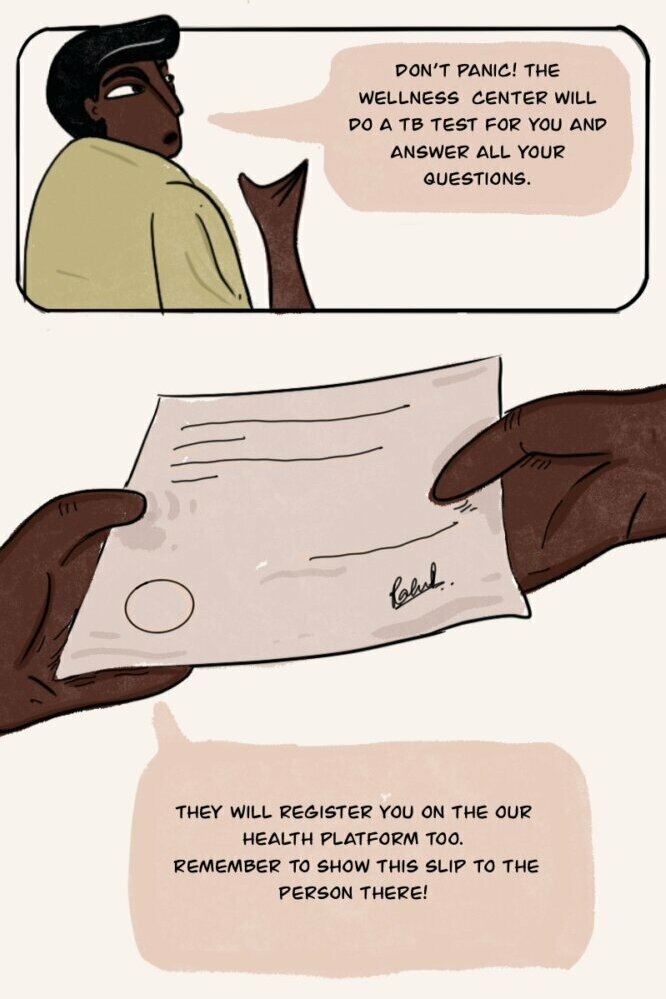

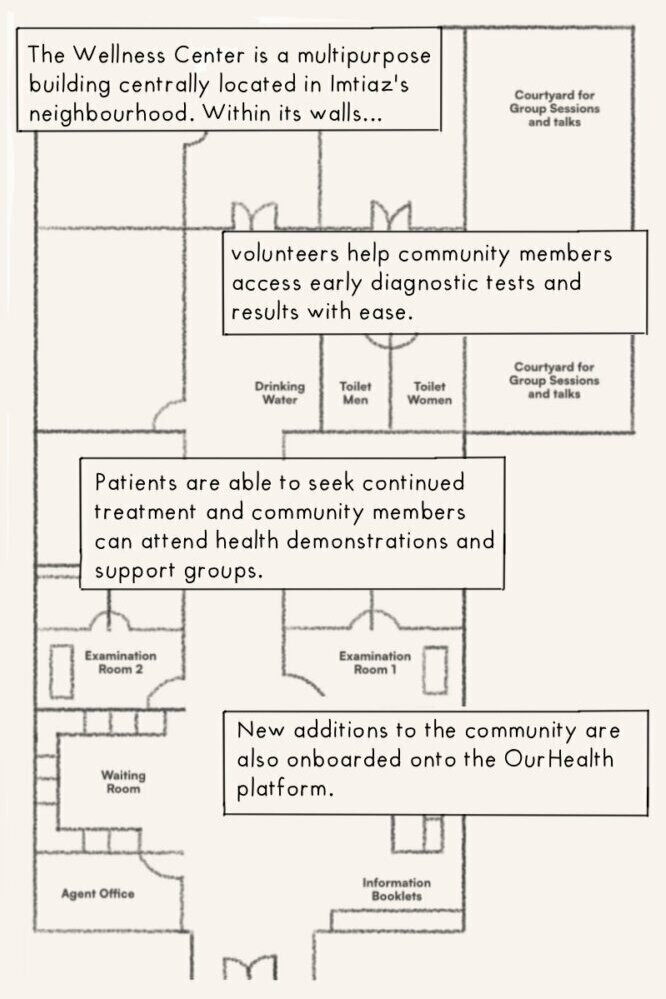

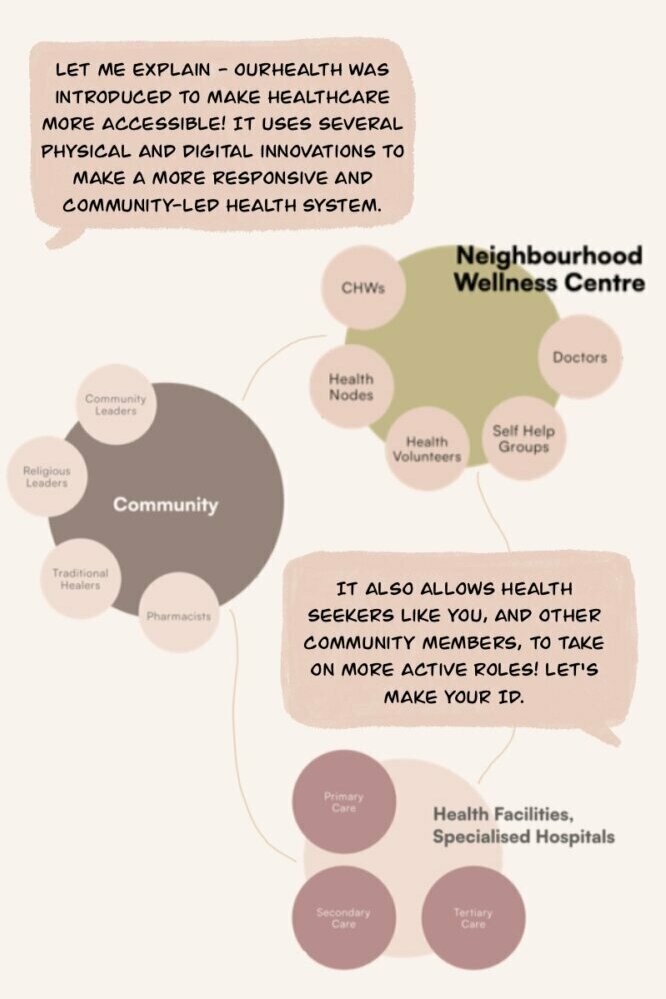

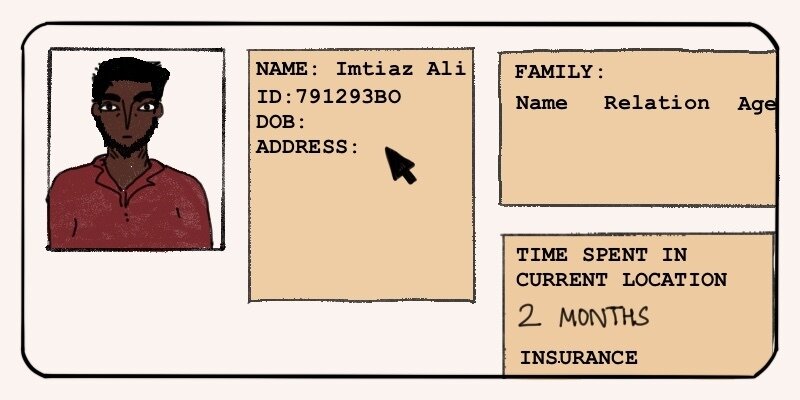

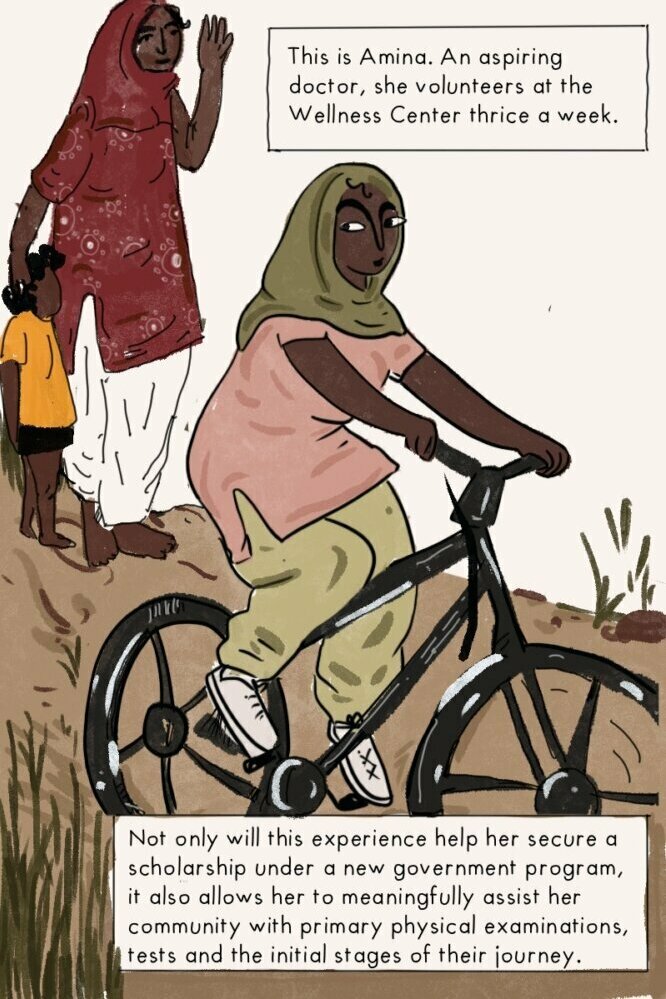

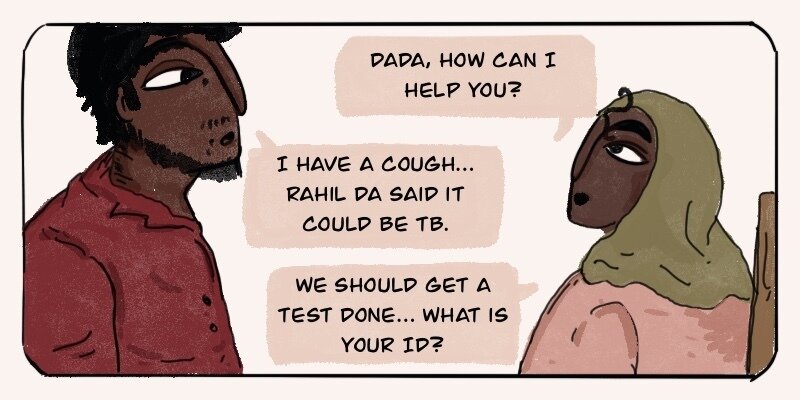

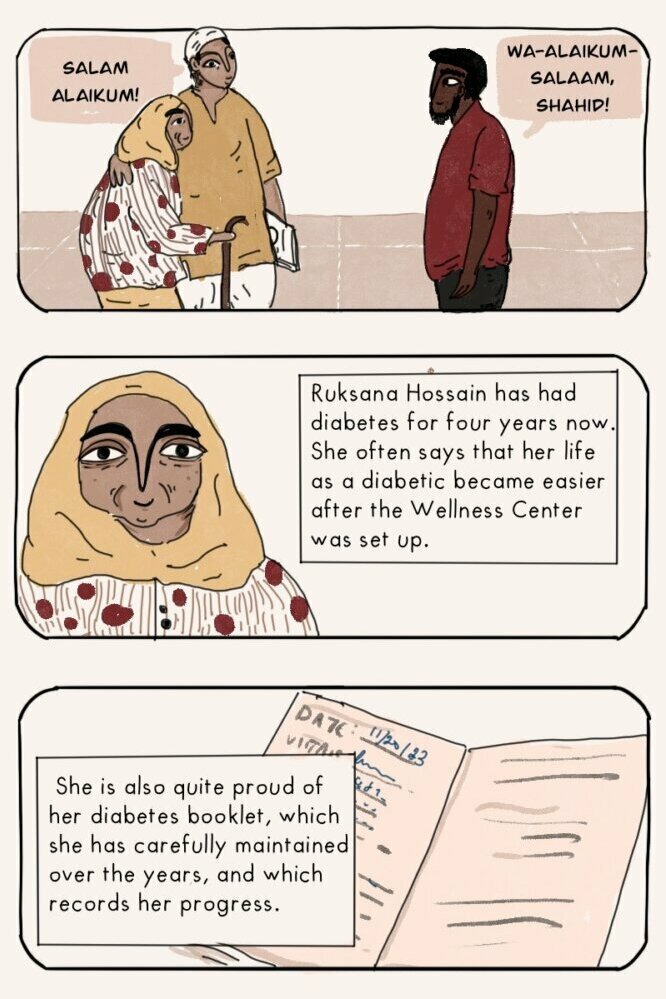

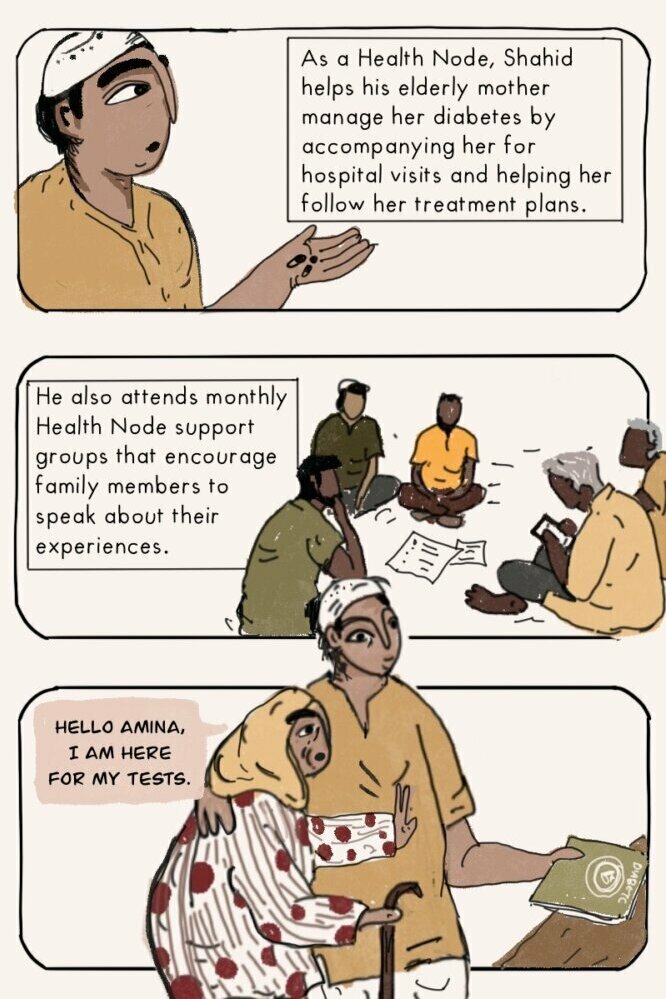

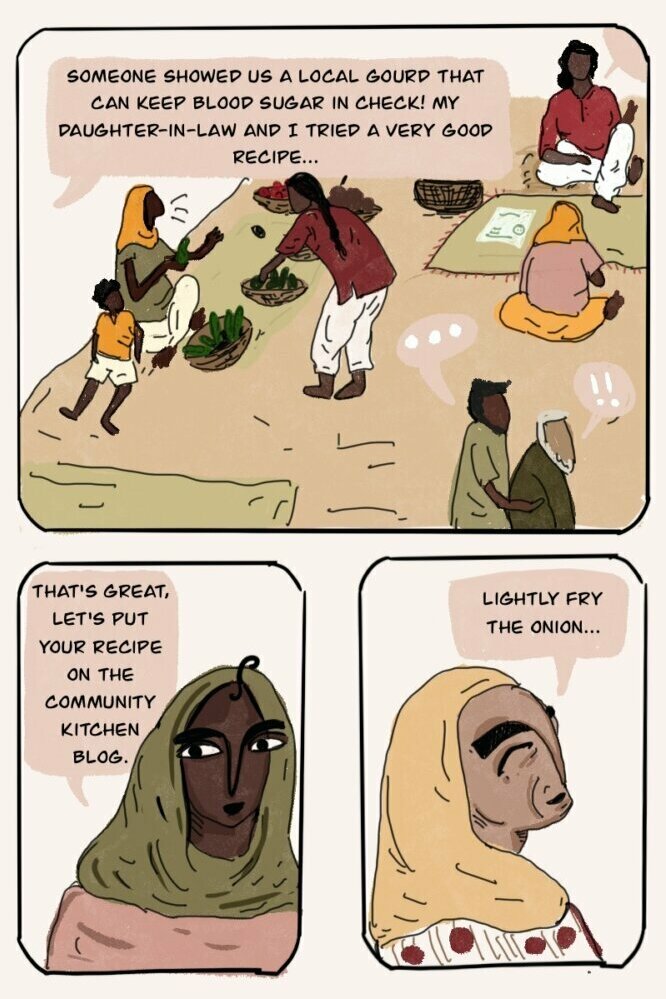

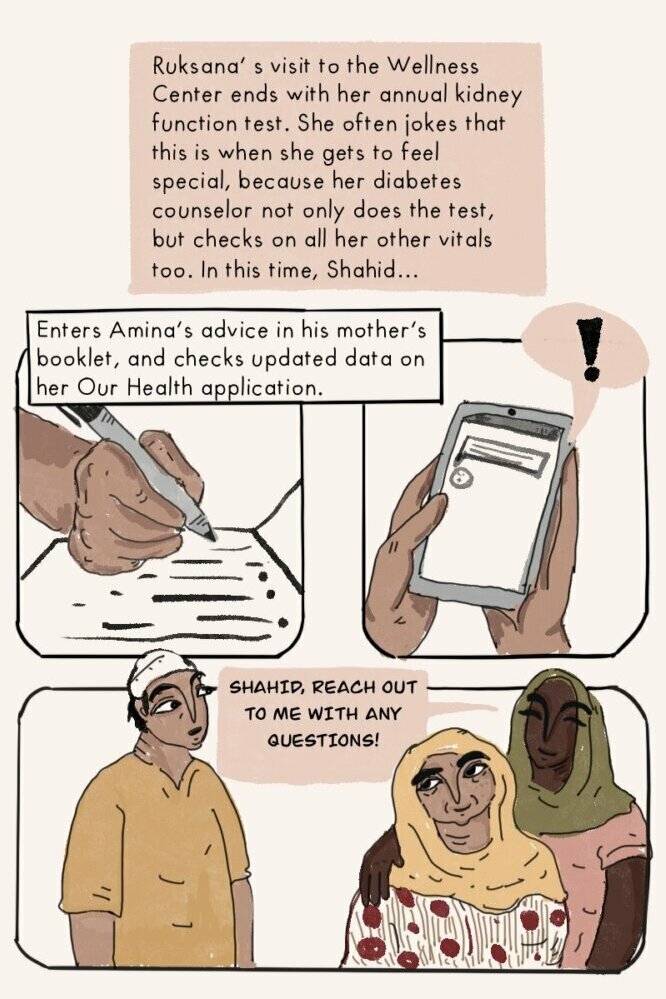

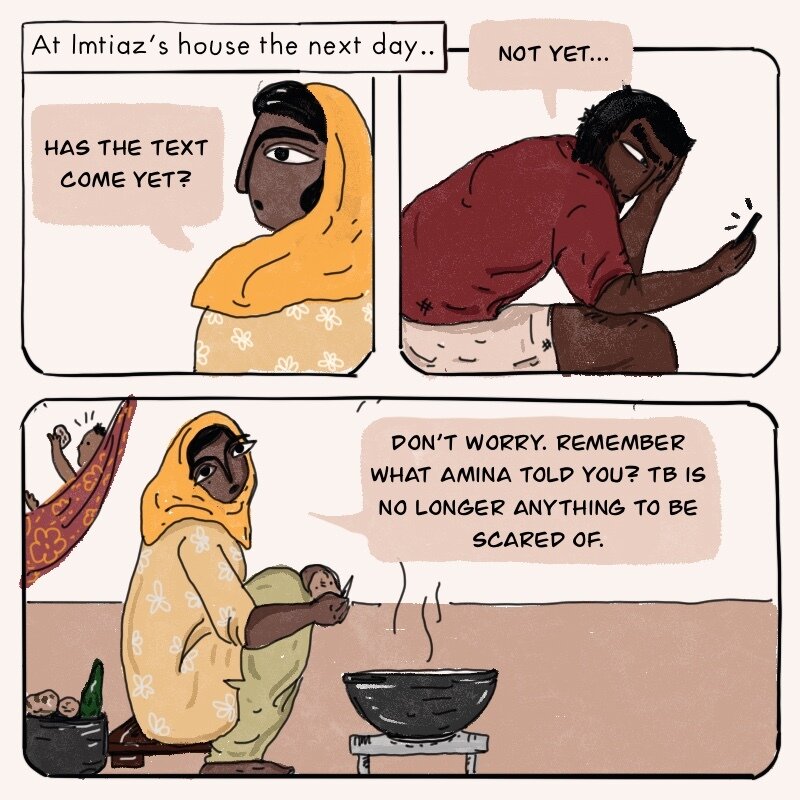

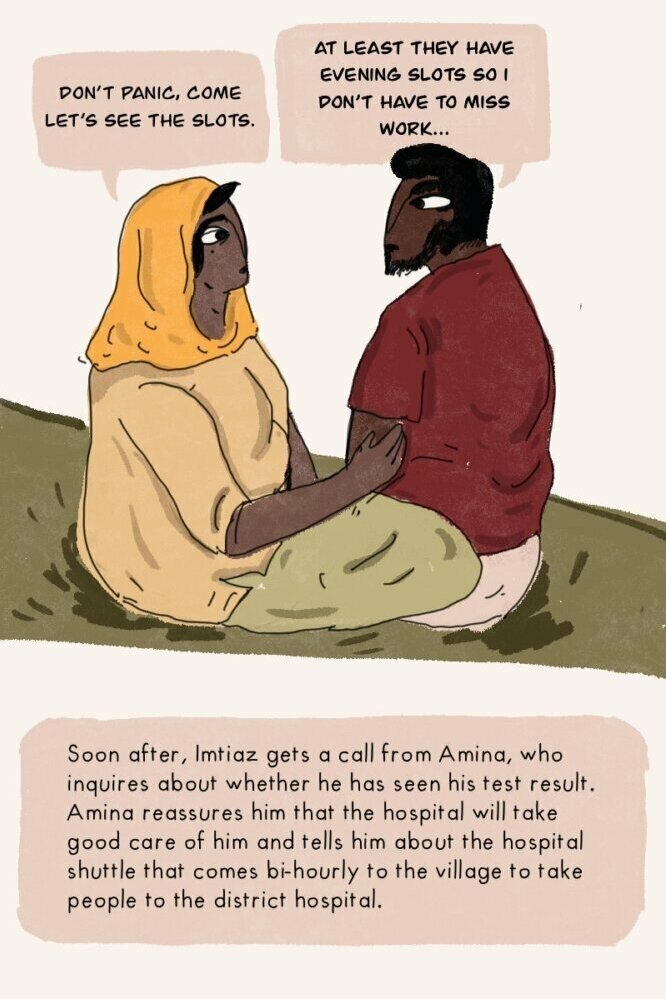

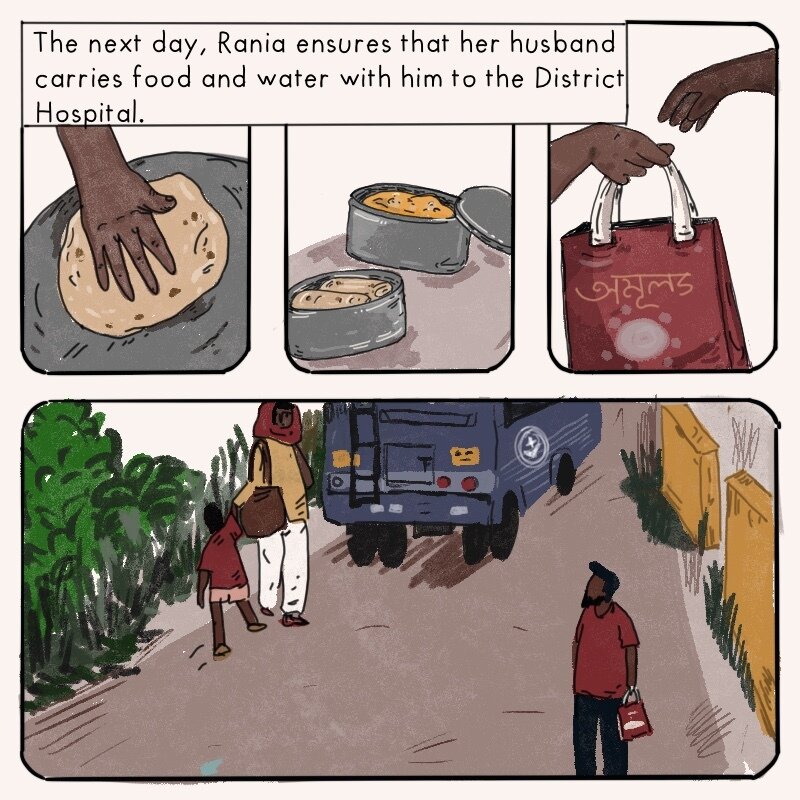

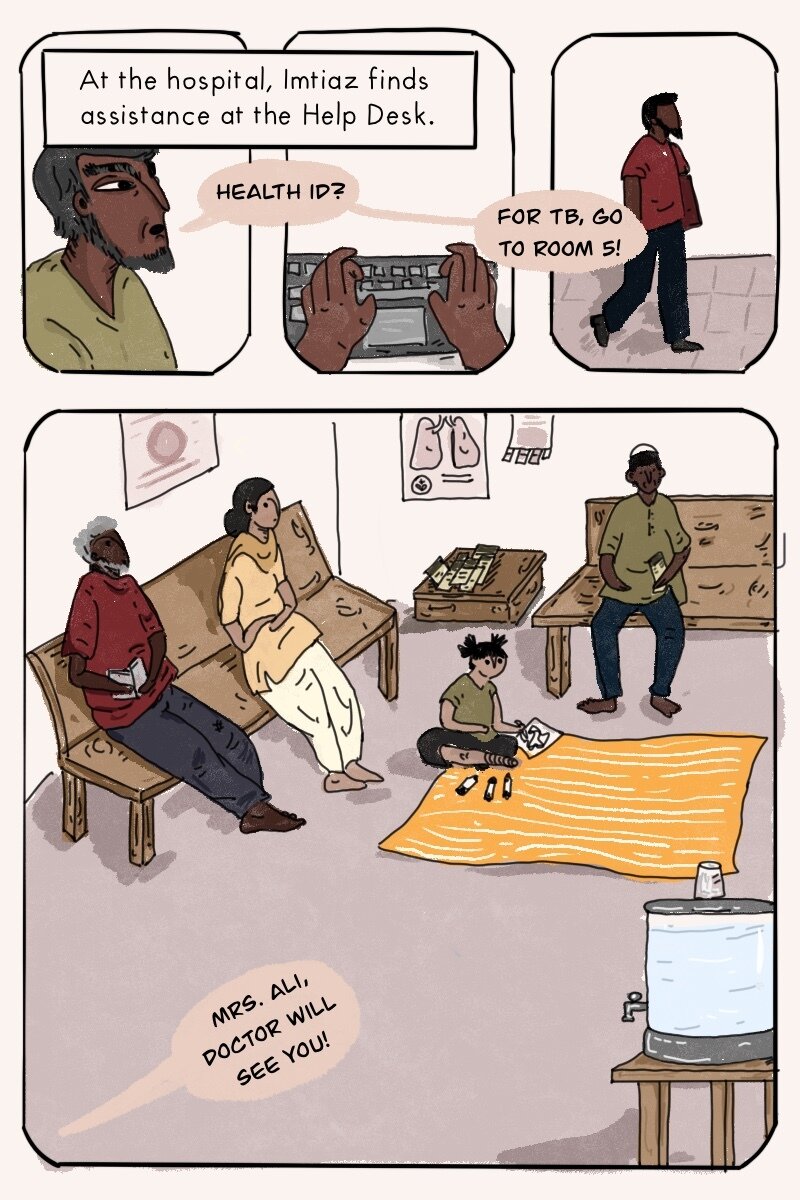

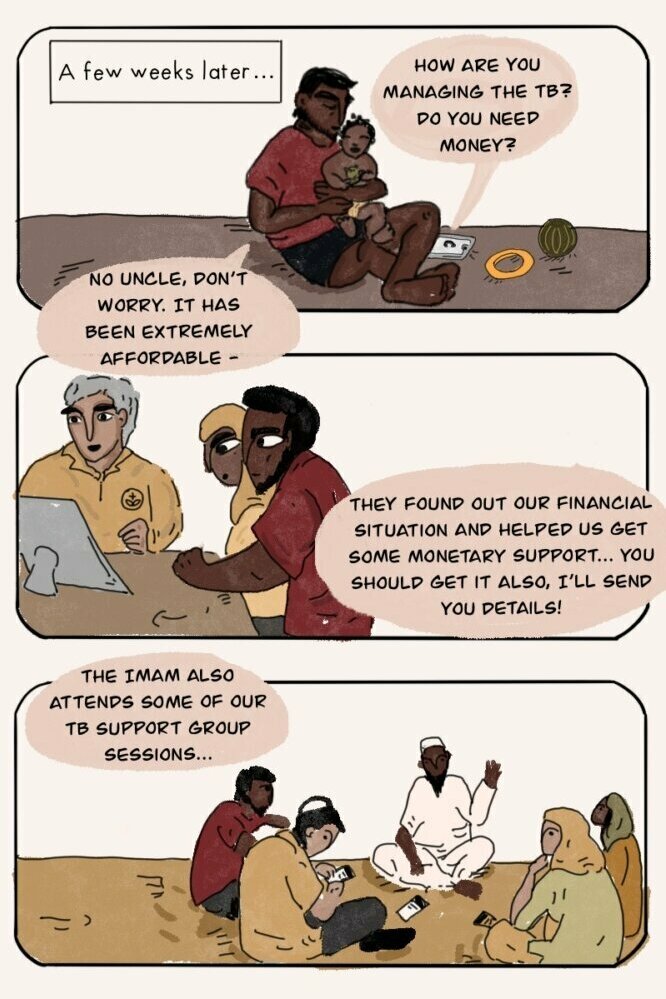

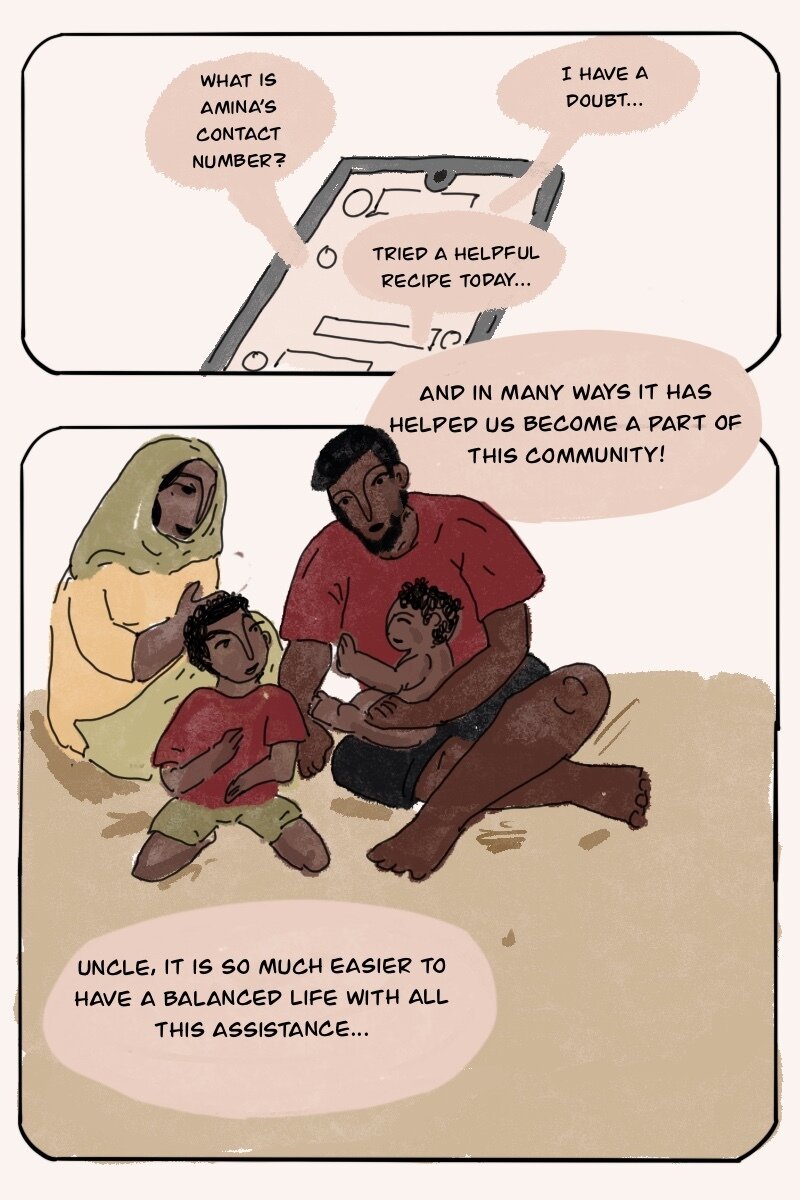

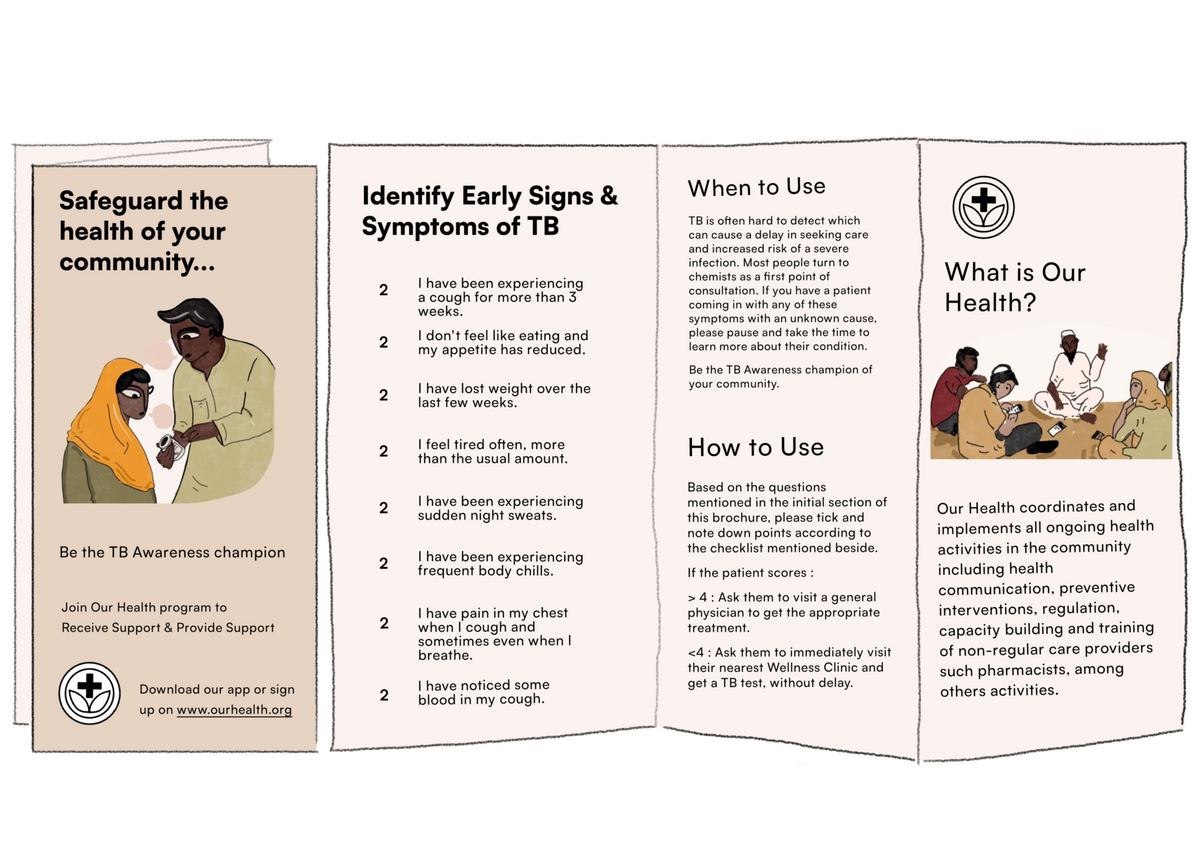

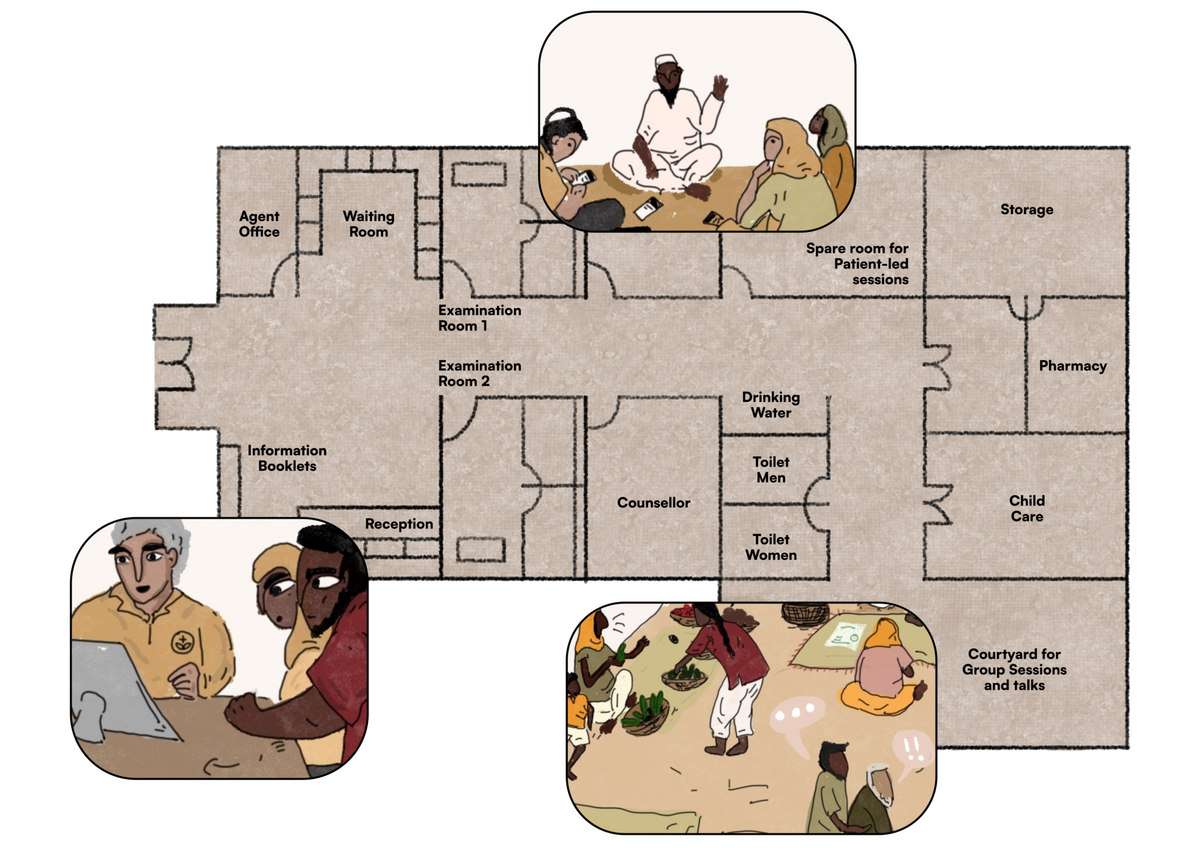

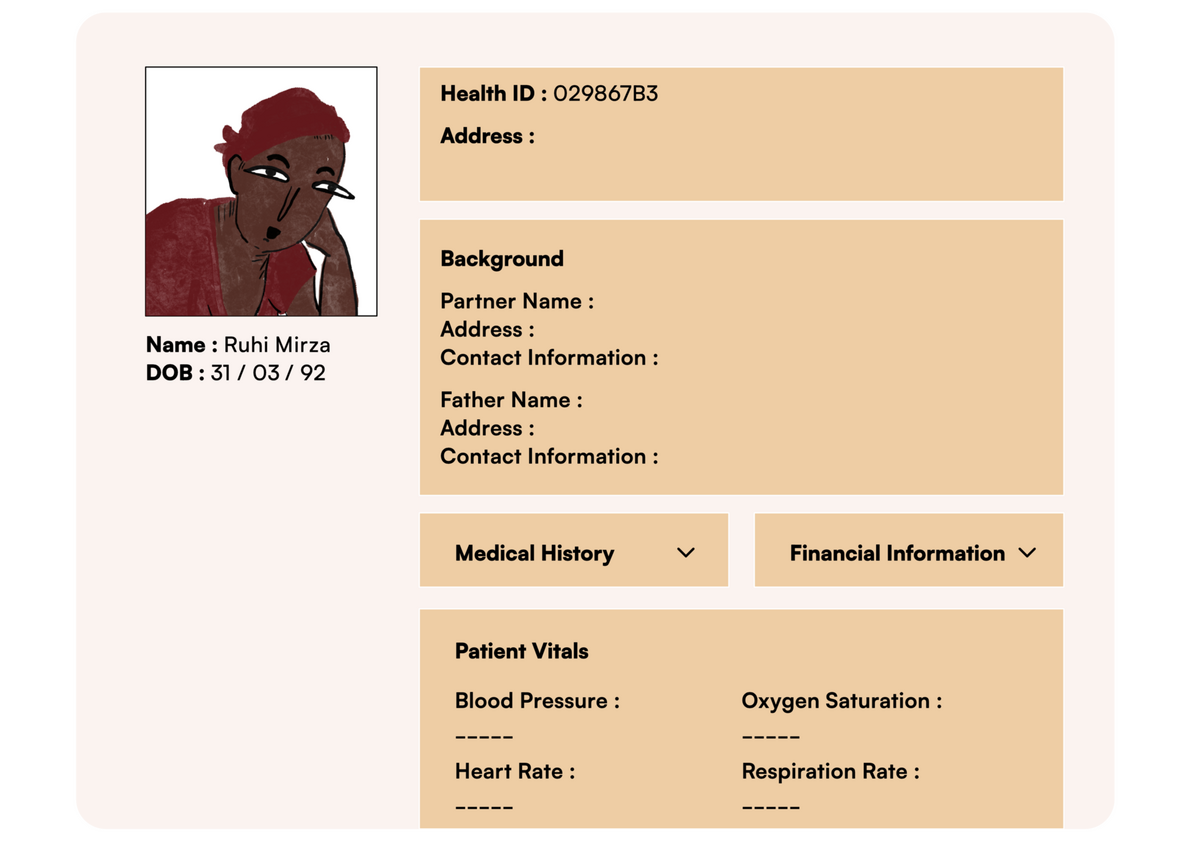

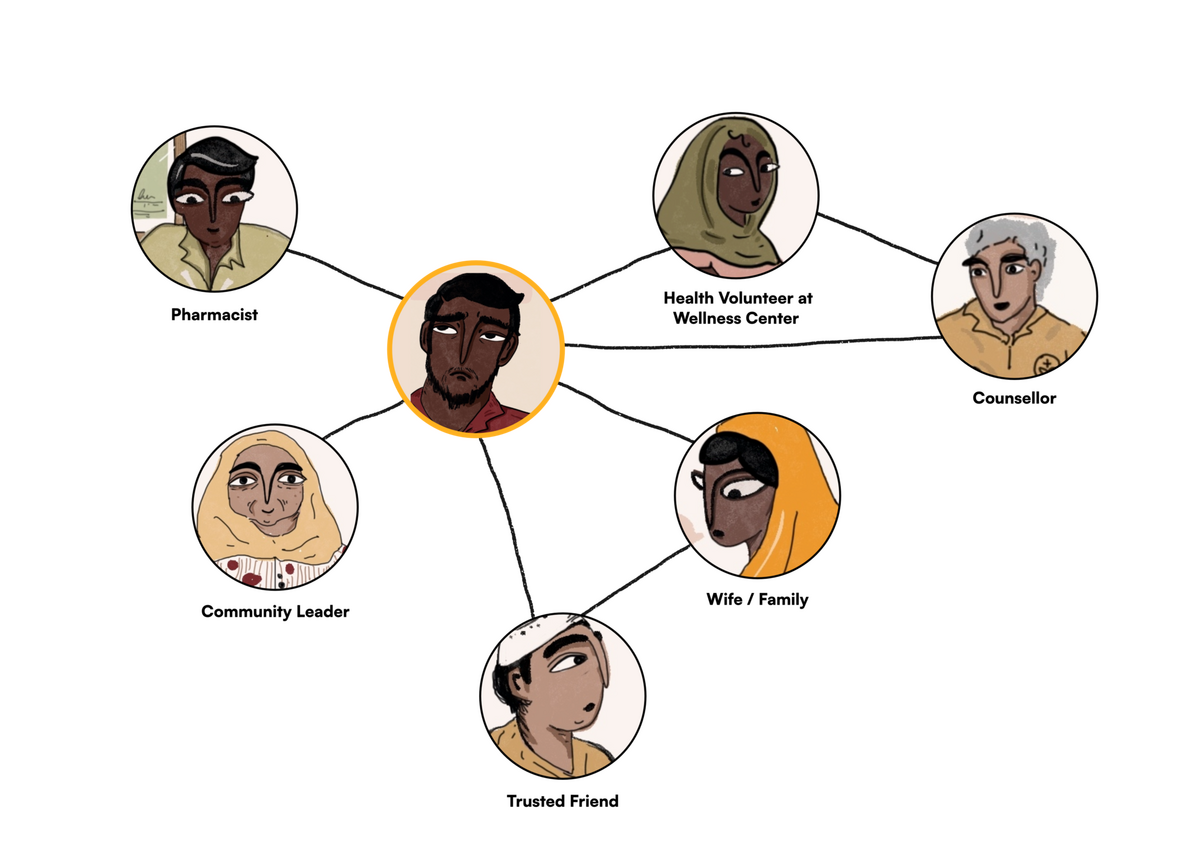

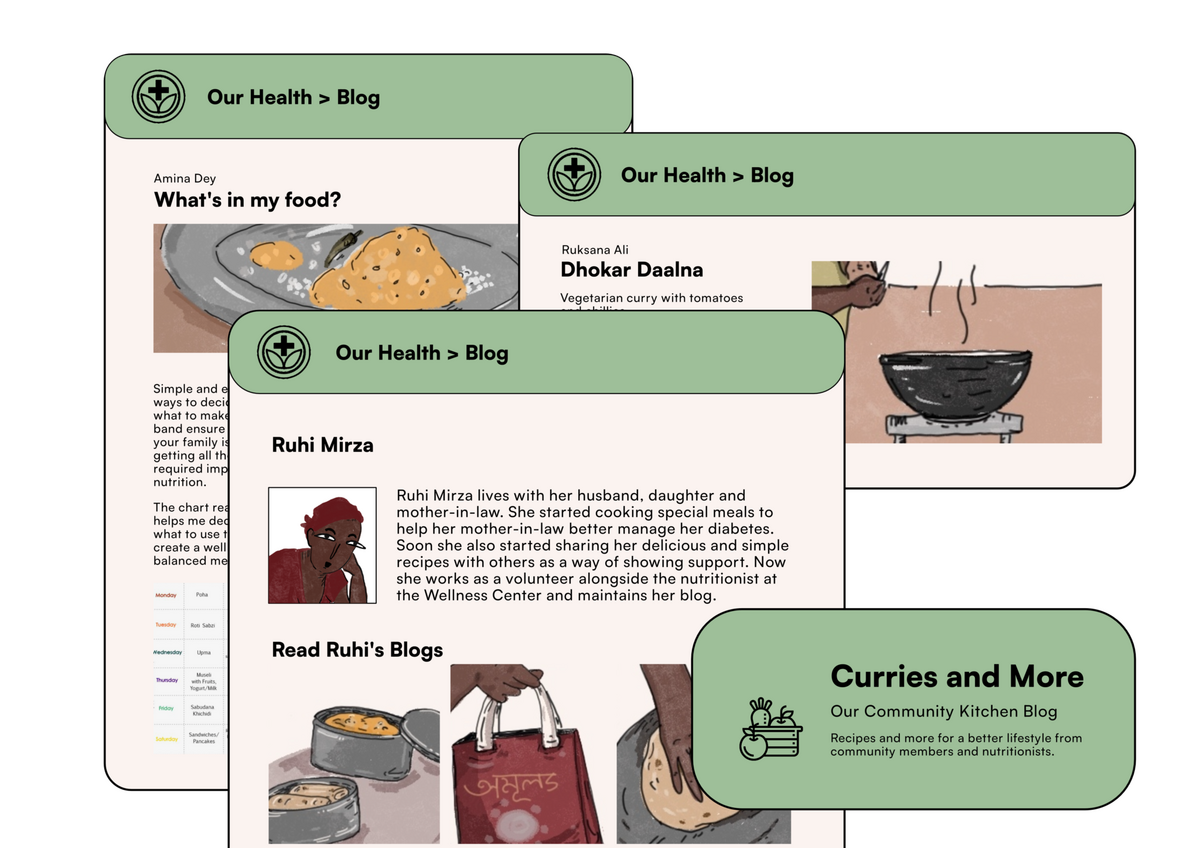

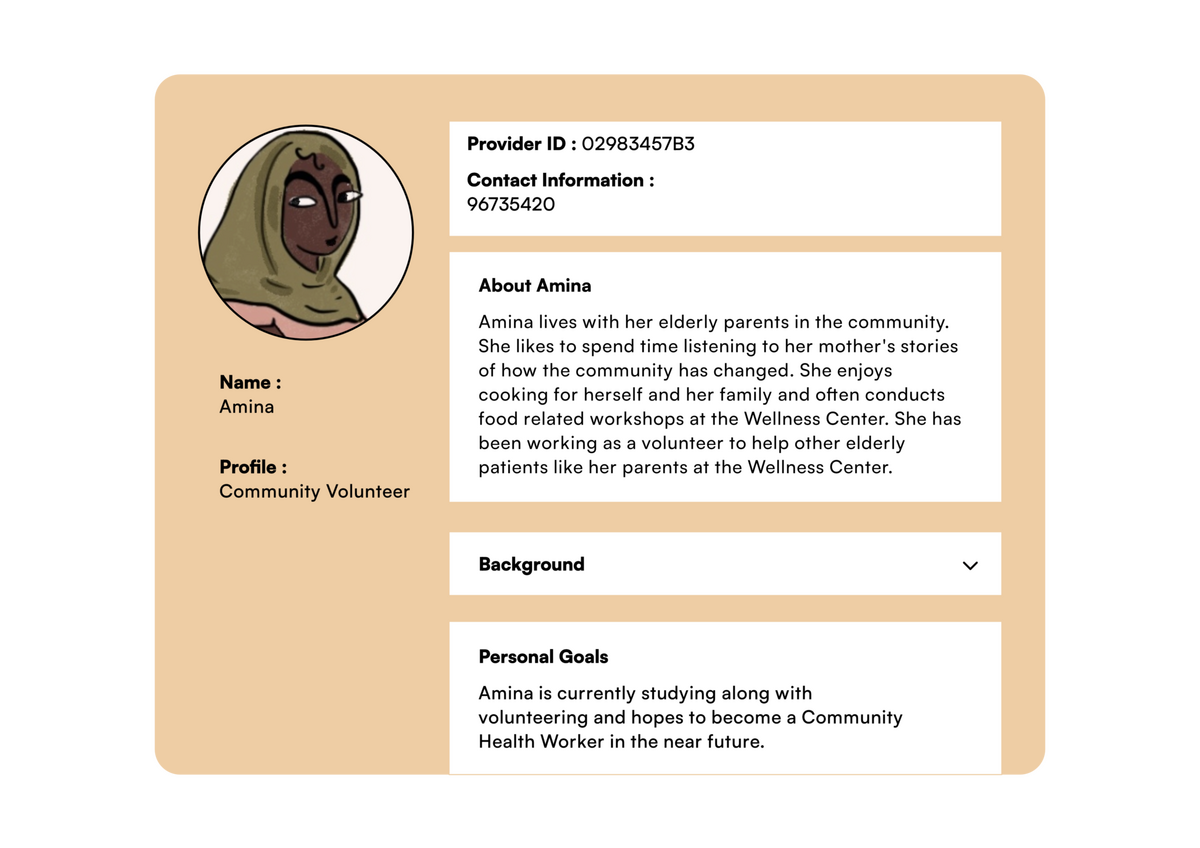

Health seekers need care and guidance in making the journey from seeker to patient, before diagnosis. They require assistance in identifying appropriate avenues of care, and often rely on their own lived experiences and those of their social networks to do so.

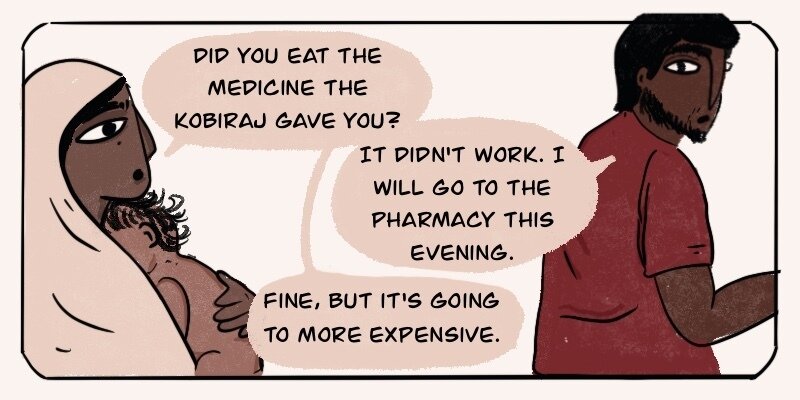

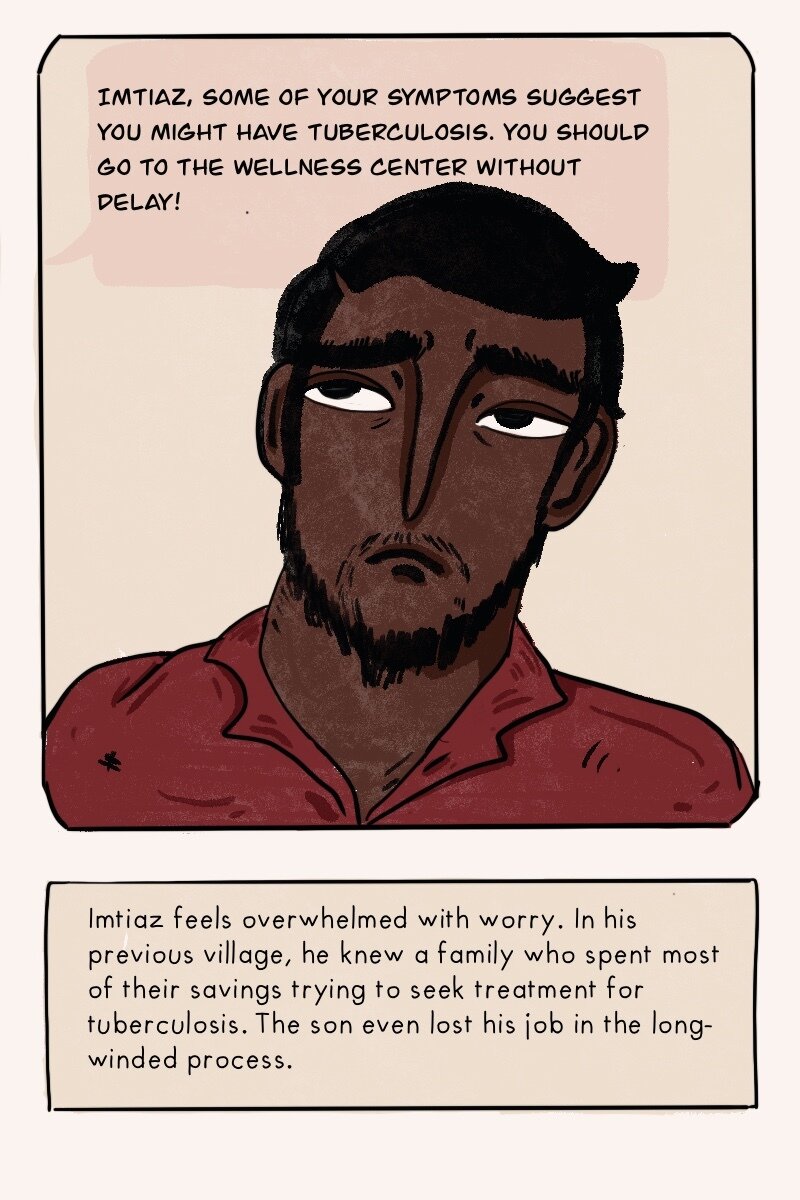

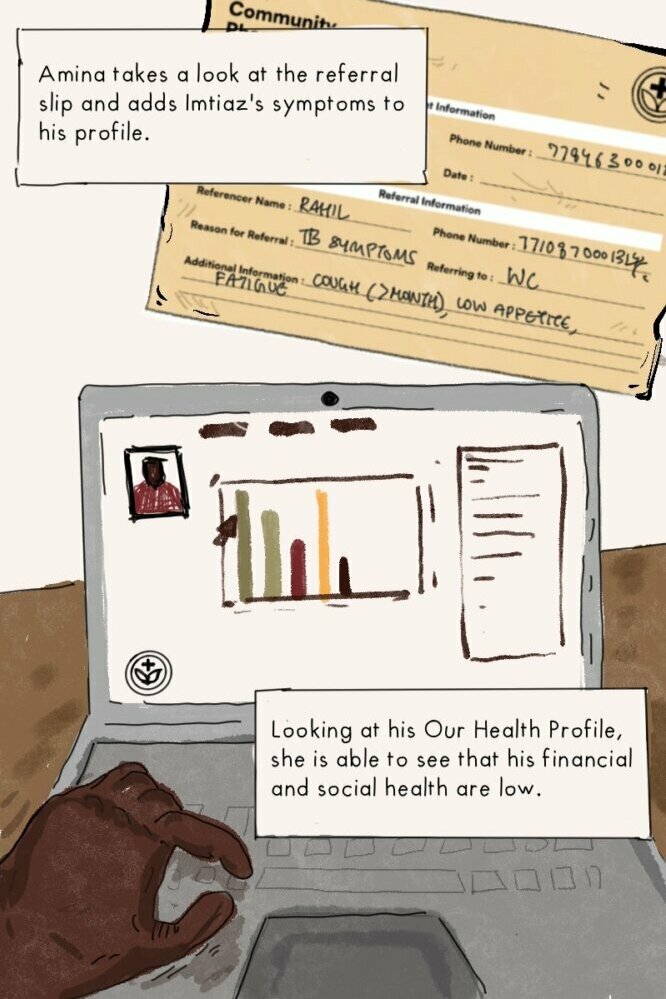

Our research finds that a seekers’ journey until successful diagnosis is often complicated, and comes with high physical, emotional and financial costs. Since the system is often only equipped to recognise a patient after a successful diagnosis, patients are left to navigate the initial stages with minimal formal guidance, causing delays in treatment and presentation of care. In some cases, seekers even turn to alternate, more accessible, forms of care.

This leads to great out-of-pocket expenditure for the seeker, a damaged perception of the healthcare system, and poor health outcomes.