Place-based Health Information

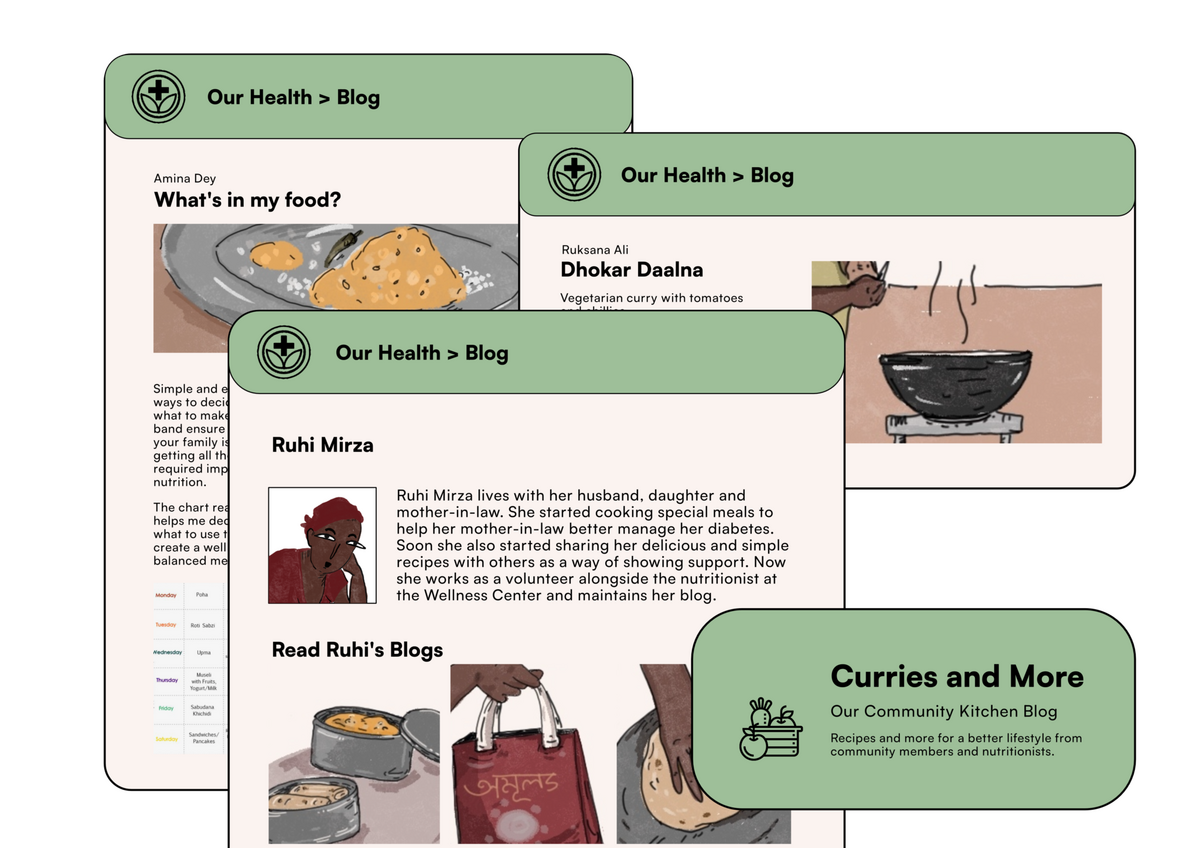

Place-based or contextualized health information refers to health information that has been adapted for the context that target communities inhabit. Such information makes it easier for receivers to understand it as it is related to the community’s socio-cultural context, further opening up a tangible path for greater uptake and action. The local cookbook blog, an example of this, is locally curated with oversight from more upstream actors. Similarly, contextualized awareness campaigns around disease burdens that are common in a community (for example TB) make them relevant and responsive to local realities.

At present, there is a conspicuous gap between how the clinical health and wellness information is communicated by the policymaker and how this information is comprehended by the community members. This disconnect may give rise to less effective policy outcomes and less desirable actions at the end-mile delivery. While there is recognition that cultural competency needs to complement technical/medical competency for public health advice to become understandable and actionable, there is limited utilization of community-level cultural competency in contextualizing health information and advice. In cases where local actors such as community-based health workers have been utilized, there have been significant gains in uptake by communities.

In the future, there should be more focus on closing the intention-to-action gap, especially at the end mile in low-income communities, with more attention to a better quality of healthcare for all. The rising disease burdens, disproportionately impacting poorer communities, will require more bias to action which might also increase focus on behavioral approaches. This would require effective health communication, which would in-turn rely on the utilization of local cultural competency.

However, there may be a number of challenges in realizing this future:

Building capacity in existing cadres of frontline workers at the local level– district, block, or village– will require resources at large scale for training and capacity building purposes. Alternatively, given the limitations of the existing health system workers, one might need to identify and invest in a trustworthy and appropriate cadre of non-clinical facilitators or volunteers. This would require financial planning for building capacity and sustaining the program at large scales and over time.

As one goes further downstream from the state level, standardization might be difficult to achieve especially when attempting to establish structures. Consistent involvement of upstream actors through regular monitoring practices should be built into the programs to ensure timely action and long-term intervention success.

Framing opportunities is an early step towards addressing these challenges.

-

How might we discover, empower and motivate reliable local actors as the last mile actors/agents of public health systems?

-

How might we apply the learnings from the successes and failures of the existing practices on contextualizing health information at the local level for vulnerable communities that have seen large demand and uptake on one hand and convenience of implementability on the other?

-

How might we imagine a monitoring infrastructure that assuages the concerns of medical experts when it comes to utilizing local cultural competencies in delivering health information?

-

How might we nudge the private sector to contribute towards meeting the capacity building costs at the local level?