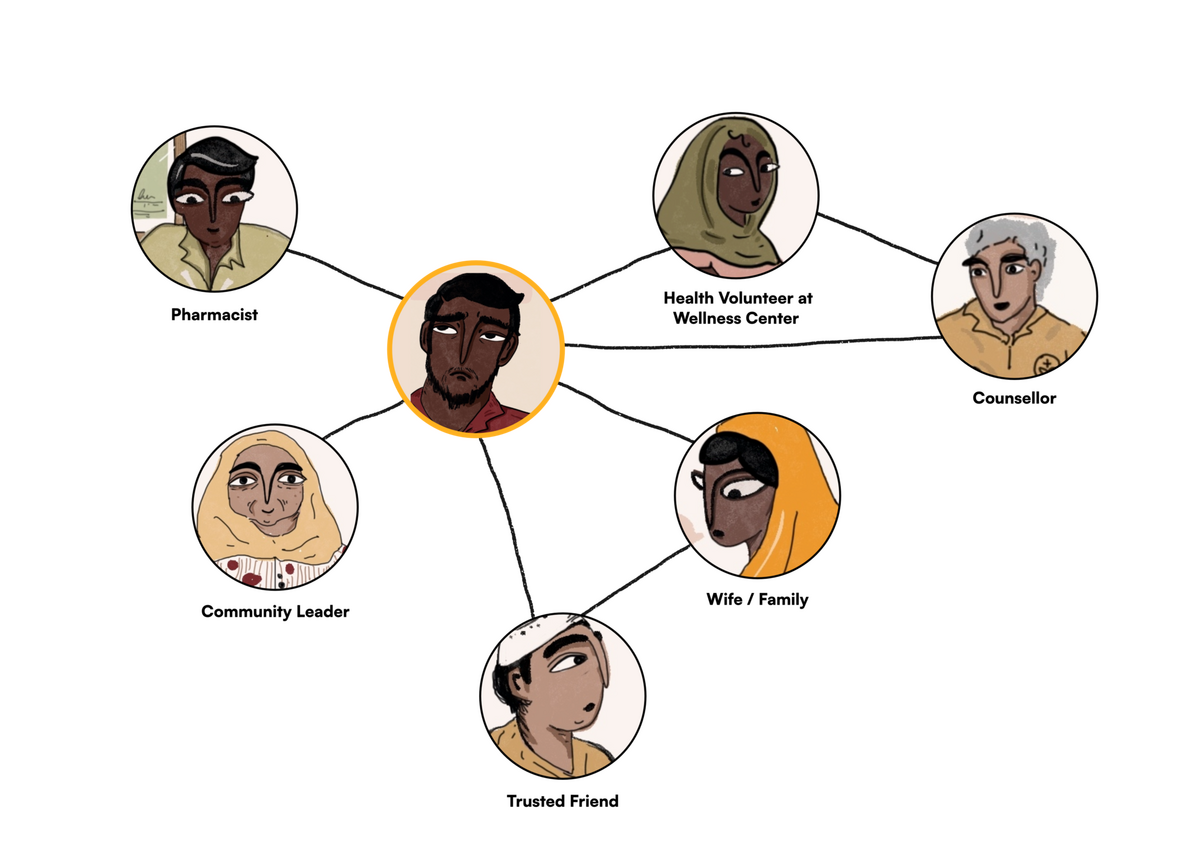

Health Nodes

Health nodes are a way of formalizing networks of care around health seekers; a network intended to reduce the burden on community health workers by bringing together family members, neighbours or friends who can potentially become a health node for the seeker. Health nodes may accompany health seekers on clinic visits, manage their health records for them, assist them with adherence, manage their health finances etc. Given the level of comfort and intimacy these actors share with the patient, there is potential to address other strands of health like emotional, social, and spiritual, which might be harder to address institutionally through formal structures of care.

There have been some initiatives on leveraging the network around health seekers but these have mostly been few and far between and limited largely to the frontline healthcare workers network. Evidence shows that in a few similar interventions factors such as poor user experience and low quality services have resulted in reduced trust in the system and low levels of adherence, which have contributed to limited success of such interventions. Noora Health’s model of empowering families to provide continuous patient support and positive patient health outcomes remains one of the few examples showing considerable impact across India and Bangladesh. While literature identifies and acknowledges the role of family members during hospital visits and stays, there is little recognition given to them by the health system in practice.

In the future, there is a scope of including the immediate family and friends of the patients as they already play a supportive role in the patients’ care journey. With rising chronic disease burdens, challenges around adherence will rise and the role of the immediate care network around chronic disease patients will only become more crucial. In developing countries it is observed that family members and neighbors stay in close physical proximity, increasing the opportunity for such interventions to work successfully. In the future, these network members can be supported with capacity building and oversight by the system actors.

Given the current role of frontline workers and the burden on them, there is an opportunity to explore ways in which they can work with informal caregivers, such as family members, and further equip them with the right tools. This will ensure that the frontline workers themselves are not overburdened while leveraging the relationships they have developed with the caregivers over time.

Additionally, in the future, these caregivers in the informal networks can be brought together through communities of practice where they can learn from the lived experiences of the other caregivers and also provide emotional support to the ones going through similar experiences.

There might be certain challenges that should be taken into consideration before the implementation of the plan:

One of the key benefits of recognition of informal care networks is capacity building, whereby care providers such as family members are empowered through training and support by the public health system. This will likely require further investment, which could make the concept unsustainable, particularly in very resource-constrained environments where public health investment may be prioritized for other needs.

With the recognition of informal care providers comes the regulatory burden for already understaffed public health systems.

While care networks might seem equipped to deal with patient-related responsibilities, the psychosocial well-being of the care providers is also an important concern. The role of caregivers can be demanding especially as most of this burden invariably falls on the women within these networks.

Framing opportunities is an early step towards addressing these challenges.

-

How might we enable and empower the health workers to support and equip the informal networks of care of the patients?

-

How might we create a support plan for the caregivers so that they feel safe, equipped, and supported?

-

How might we create channels between the informal caregivers and the formal health workers?

-

How might we standardize and scale a good quality care support plan across geographies?

-

How might we work with the frontline workers across geographies to design and deliver such a plan taking into account the varying local contexts in LMICs?

-

How might we explore the creation of communities of practice between care providers?